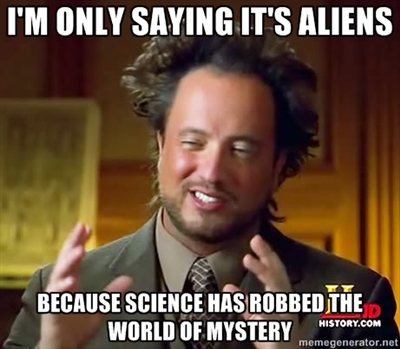

Giorgio Tsoukalos, star of the History Channel’s “Ancient Aliens,” father of an internet meme, and owner of a great head of hair.

********

“As we know from ancient Egyptian history, [UFOs] are manifestations of psychic changes which always appear at the end of one Platonic month and at the beginning of another. Apparently they are changes in the constellation of psychic dominants, of the archetypes, or ‘gods’ as they used to be called, which bring about, or accompany, long-lasting transformations of the collective psyche.”

~Carl Jung

********

I’ve spent hundreds of hours of my life watching documentaries about things that I don’t believe exist. There is a sizable stretch of cable television dedicated to deadpan explorations of ghosts, aliens, Bigfeet, psychics, and dozens of other creatures of dubious reality, and judging by the cultural footprint of these shows, it’s clear that I’m not alone in my regular excursions onto this paranormal turf. The History Channel’s Ancient Aliens—arguably the crown jewel of the genre—has inspired an internet meme, provoked a South Park parody, and put up ratings that top Real Housewives and It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia. If you’re an American with cable TV, odds are good that you could find an episode of MonsterQuest, Paranormal State, The Nostradamus Effect, or Ghost Hunters airing right now.

These programs form a kind of Paranormal Edutainment Complex (PEC) that incorporates the audience, the studios that put out these shows, the channels that air them, the talking heads that reappear across different programs, and a cottage industry of books, films, and tourism centered on the featured subjects. Even Hollywood has seized the opportunity to make some cash by blurring the line between its own sci-fi and the PEC’s psi-sci. Last summer, Universal Pictures collaborated with Ancient Aliens to create a tie-in episode based around the big-budget camp spectacular Cowboys & Aliens.

PEC shows share an at least aesthetic adherence to the trappings of hard science and of heavily scientized fields of research like archaeology. Their “evidence” is designed to resemble, well, evidence. You’ll see, for instance, plaster casts of Bigfoot footprints, EMF readers beeping at spectral presences, and carvings of Mayan gods interpreted as records of alien contact. The kitsch factor of these shows is undeniable—observing prophecy expert John Hogue’s physical transformation into a facsimile of his beloved Nostradamus has in itself provided enough entertainment value to make my time spent with this genre worthwhile—but I think there’s more going on in the PEC than goofy fun and paranormal wish fulfillment. In their style and aesthetic, these shows are embodying and responding to cultural anxieties about science and its privileged role in arbitrating what does and does not constitute knowledge.

PEC programs promote a kind of epistemological populism. Mainstream scientists are cast as either drones blinded by their own assumptions or conspirators actively covering up the truth. The role of hero is reserved for amateur and outsider researchers. These researchers proudly tout the supposed evidence they collect and the alleged rigor of their methods, suggesting that it’s not science qua science that the PEC takes issue with, but scientists as a class. Science qua science, after all, has established itself as the gold standard for knowledge. Its tangible accomplishments (penicillin! man on the moon! cloned animals!) are flabbergasting. They appear concrete and legitimate in a way that the diffuse and discursive achievements of the arts, humanities, and spiritual endeavors do not. The resulting dominance of science—questioned in May by Philip Kitcher’s “The Trouble with Scientism” in The New Republic—has essentially forced non-scientific groups to at least superficially adopt scientific language and style of presentation. Even Christian fundamentalists, often framed as the enemies of science, seem to have conceded that they’ve lost the battle over rhetoric. Intelligent design theory, for example, paints a patina of science over religious creationism, and bestsellers like A Case for Christ attempt to make an empirical argument for the divinity of Jesus. Even if the impetus for their beliefs comes from a place of blind faith, fundamentalists realize that appeals to science are necessary when they venture outside the church and deal with skeptics and fence sitters.

Though most scientists might scoff at these efforts as they scoff at the claims put forward by the PEC, the fact that Christian groups are using this rhetoric represents a kind of victory for rationalism and reason. Even those with the most unscientific claims feel compelled to justify themselves through the language of science. Pointing to the Bible or to one’s own perceived experiences with the supernatural is no longer enough to make a valid claim to knowledge. You need evidence, and this evidence’s credibility is determined by its apparent adherence to parameters laid out by science.

This dominance is complicated, though, by the reality that, for most Americans, science is something of a black box. Scientists (God knows who) conduct experiments (entailing God knows what) and then issue reports that detail their conclusions (arrived at God knows how). Imagine that someone handed you two scientific reports, one that supports the concept of human-driven global warming and one that disputes it. Without falling back on the presumption of a scientific consensus for the former, could you determine if one study was sound and the other faulty? If you could, wonderful, but I suspect that the vast majority of us—myself included—could not. The esoteric nature of sciencespeak makes it an incredibly pliable social instrument. Since most of us are unable to differentiate what constitutes good science or bad science, we simply find a scientific-sounding explanation that supports whatever it is that we want to believe, even if that something is the existence of Bigfoot.

Check out the sweet science gear on these Bigfoot hunters.

And it’s important to realize that even if we could scour every inch of the Pacific Northwest and conclusively show Bigfoot doesn’t exist, Bigfoot would not go away. Many of us want to believe in myths. A world full of monsters and a sky full of aliens feels rich and mysterious in ways that the material banality of scientized existence does not. Even beyond this aspect of simple pleasure, folkloric thinking has value. Ghosts help us to consider our mortality and give shape and focus to the traces our loved ones leave behind when they die. The apocalyptacism of Nostradamus provides a chance to meditate on time, history, and free will and to vocalize anxieties about a world that pretty much always feels like its about to fly off the rails. The Grey ETs—those huge-headed, almond-eyed space invaders—can themselves be read as imaginative responses to the dominance of an unreflexive scientific mindset. They look like us, but with bigger brains, astonishing technological prowess, and an amoral lack of concern for their abducted subjects/victims during their sinister experiments. Like literature, myths provoke and help us to process important concerns, and like literature, myth has been largely demoted from its former status as an important tool for understanding life and the world.

Many of us, however, are not finished grappling with the issues surfaced by myth or with the evocative images and narratives that myth provides. Polls generally show that one-third to one-half of Americans believe in ghosts and God knows how many others, like me, would prefer to believe if it weren’t for the gnawing condemnation of the scientific establishment and the attendant fear of being thought an idiot. We want ghosts, dammit, and we want them taken seriously by the culture in which we live (meaning neither horror movies nor academic essays on The Turn of the Screw are enough). But if the only way that the mythic can find voice is through the language of science, then we shouldn’t be surprised when people start chasing spirits with infrared cameras, and we shouldn’t scoff either.

In popular perception and, at least to some degree, in reality, science is an imperial project, seeking to colonize every crevice of the human experience and explain it on its own terms. Love and altruism are configured as evolutionary adaptations. There are scientific journals dedicated to “empirical studies that apply scientific stringency to cast light on the structure and function of literary phenomena.” We’re told that the abstract artworks we like best are attributable to their 20% redundancy of elements. I’m not saying that there is something inherently sinister about quantitative work on topics that have generally been the purview of the humanities. My concern is that numbers will continue elbow qualitative thought out of the conversation on issues that cannot be adequately interpreted through the scientific method. Whether the folklore centers on Mt. Olympus, faeries, or of Little Green Men, there is insight to be gleaned by interpreting the world poetically and mythopoetically. And when the myth feels forced to resort to the language of science, both myth and science lose.

Science, too, has suffered from allowing its rhetoric to become ubiquitous. Since we all have to use scientific language anytime we make a claim to knowledge, we’ve bent it to a point of near limitless flexibility. We’re all so accustomed to using it as a tool to argue for pre-existing and predetermined beliefs that never needed to be scientized (ghosts, God, the goatman) that on issues where science is invaluable—proving that climate change is real and human-driven, for instance—it can feel natural and, for many Americans, even convincing to fall back on whatever science-ish arguments validate the side of an argument they’d prefer to be on. It bears mentioning that not every scientist is trying to drain the world of its spirit and its mystery. There are chemists who love Romantic poetry, physicists who are religious mystics, and biologists who believe in ghosts. This problem is cultural. The popular press, politicians, everyday people, many mainstream scientists, paranormal researchers—we’ve all given science a special claim to knowledge that its never fully earned.

The PEC is, in its way, a product of the scientific project of attempting to synthesize the unsynthesizable. We need access to the fantastic, not just on the order of individual pieces of fiction, but on the order of myths that we absorb, co-create, and reimagine collectively. They give us a cosmic, cognitive toolkit to work through life and love and death and disappointment. They give us a language to discuss these things that feels suitably epic and mysterious instead of anesthetic and reductionist. I doubt if these impulses can be successfully integrated into the scientific style of knowledge-craft. Capital-S Science is unlikely to ever welcome prophets and monsters into the fold, and yet prophets and monsters will never disappear. By resorting to science’s own rhetoric, the PEC works to buttress the monopoly on understanding that we’ve largely ceded to science. However, it also subverts it. It questions the right of any small cadre, no matter how smart or educated, to dictate the substance of reality. The PEC won’t let them take away our ghosts, our mystery, our magic, and for that, I guess I owe Ancient Aliens a debt of thanks.